RAJASTHAN

PLUG-IN CITY

PLUG-IN CITY

Architecture as a tool to combat space scarcity

while preserving socio-cultural roots

while preserving socio-cultural roots

INVESTIGATING HIGH-DENSITY DWELLING & VERNACULAR ARCHITECTURE

Amid the predominantly narrow street lanes crisscrossing Rajasthan’s high-density dwellings, I noticed an interesting paradox: building orientations that underutilize precious space. This sparks a more specific question on how the utility of certain space—for instance, particular areas of a building facade—could be better maximized.

In my simultaneous exploration of building facade and Rajastjan vernaculars, I chose to focus on the Haveli, arguably one of its most complex and interesting buildings. Typically, Havelis are 3-4 stories private residence originally build by the rich merchants or nobility who want to imitate the lifestyle of royalty (Figure 1.1). Particularly intrigued by the fact that Jalis (usually perforated window screens made out of sandstone or wood) are carved into specific patterns with thoughtful meanings like loyalty and dignity, I would later incorporate this spirit into my design concept.

VISUALIZING A PLUG-IN CITY

Micro parasitical unit is a novel architectural language that refers to a relatively small building structure that can be attached to a larger building. With severe space constraints in Rajasthan, this may serve as a possible solution without the need to invade new plots of land. In order to also preserve the local vernacular identities from the past, I attempted to design such micro parasitical “plug-ins” using the inspiration from the haveli and jali.

Concurrently, noticing how the lack of public waste disposal facilities and indiscriminate littering have contributed to city-wide hygiene and health issues,

I proposed a building waste management system aimed at encouraging behavioral change from the most fundamental city unit: the home.

The Tri-Sorter Garbage System: Essentially three separate “vertical chutes” installed at designated locations in the building and running from top to bottom floors, with three unique “garbage disposal slots”—for plastic, organic, and general waste—on each floor.

- Plastic Chute (orange): Connected to a machine capable of sorting plastic products into different polymers and compressing them into pellets (later transported to recycling factories).

- Organic Chute (green): Connected to a machine capable of turning organic wastes into fertilizers (later used in domestic agriculture)

- General Chute (red): Connected to an external garbage storage (scheduled for weekly pick-up by city garbage truck)

The close proximity of these chutes to residential units on each floor and other clear benefits (i.e. common income from sales of recyclables and fertilizers and elimination of unpleasant smell and disease-causing vectors) could encourage residents to properly discard their garbage.

During my time in this culturally rich and artistic state in the north-western region of India, what I observed—the concentration of buildings with narrow streets providing highly limited public space yet full of people living inside each—attested to the preliminary information from my research that Rajasthan falls into a critical high density area. With a population of around 68.89 million (as of 2018) and growing, this has increasingly posed issues in living conditions for many, particularly the younger generations who aspire for more independent living or simply a little more space of their own.

Taking this into consideration, along with the fascinating traditional charm I witnessed, I became determined to answer the question:

How can local uniqueness be integrated into the modern densification of building to address issues in overcrowded living conditions?

From the Jali, a type of traditional Indian window, and from the concept of micro parasitical architecture, I drew inspiration to craft the preliminary design concept for “plug-in units with uniquely Indian flavors”—a concept that may be a starting point in reclaiming not only space but also quality of life.

Beyond space scarcity, overwhelming amount of “waste” generated by Rajasthan’s growing population is also undermining quality of life, along with the natural environment. A probe into this issue—via review of research publications and on-site study—also culminated in a preliminary proposal for building waste management system.

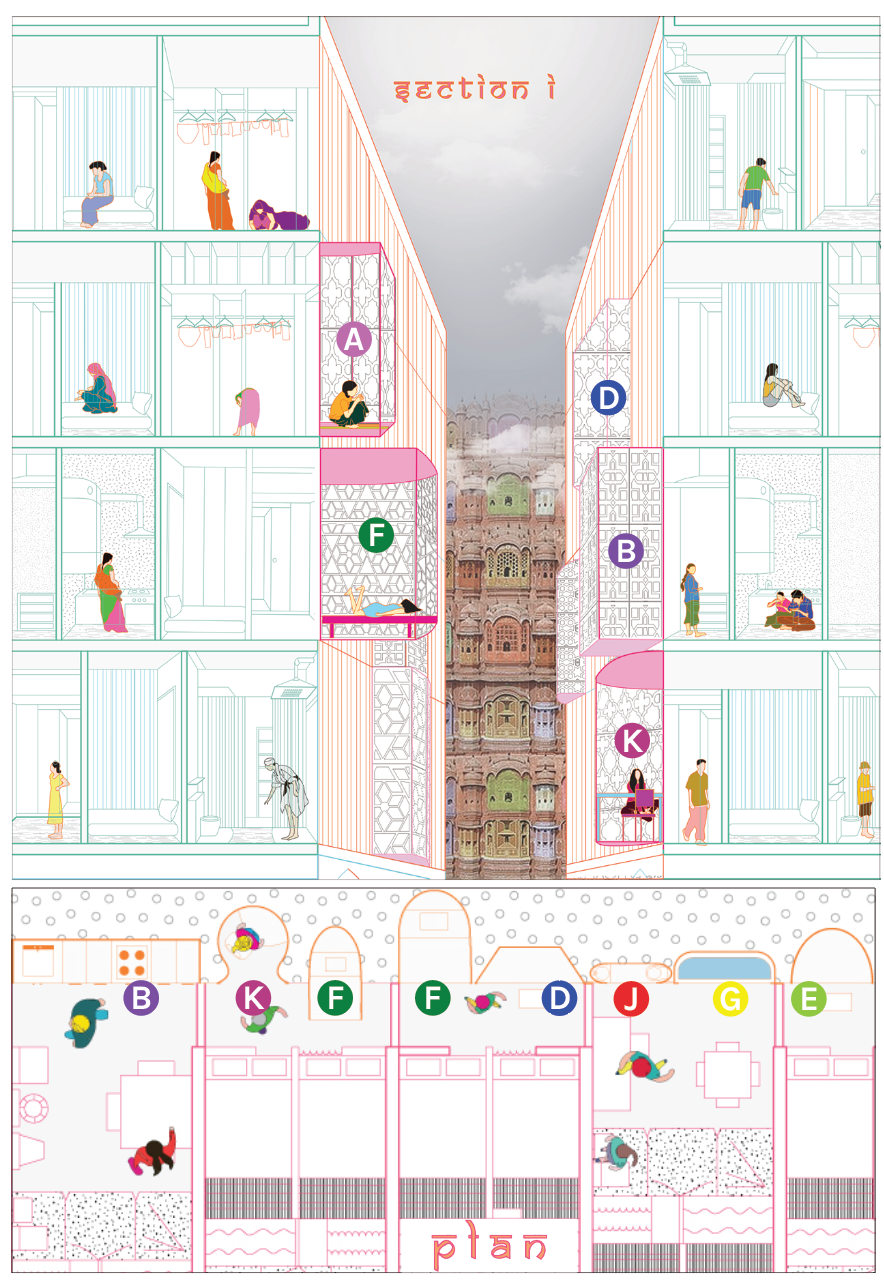

DEVELOPING PLUG-IN PROTOTYPES

With the aim of introducing modern architectural elements that respects both culture and individual needs of the population, I delved into local lifestyle and found additional inspirations. Shapes of commonly found household furniture form the basis for 11 different plug-in unit typologies, with each serving a specific purpose

By applying certain principles from the jali in the design of these plug-in models, I hope users would also gain the following benefits:

- Responsive to climatic change - the plug-in unit acts as a shade in the afternoon and allows natural ventilation to cool down the space at night.

- Enhance privacy - the plug-in unit will also act as a double wall or a filter that helps lessen the amount of light into the space. The user can select an appropriate model according to their requirement for privacy. Typically, the room with the need for high privacy (i.e. bedroom) would be suitable for a model designed with the most-dense patterns as it needs the most privacy and shade. Meanwhile, a kitchen usually requires the least dense design with the need to release smoke and smell.